Cartel Theory

- A cartel is a formal price-fixing agreement

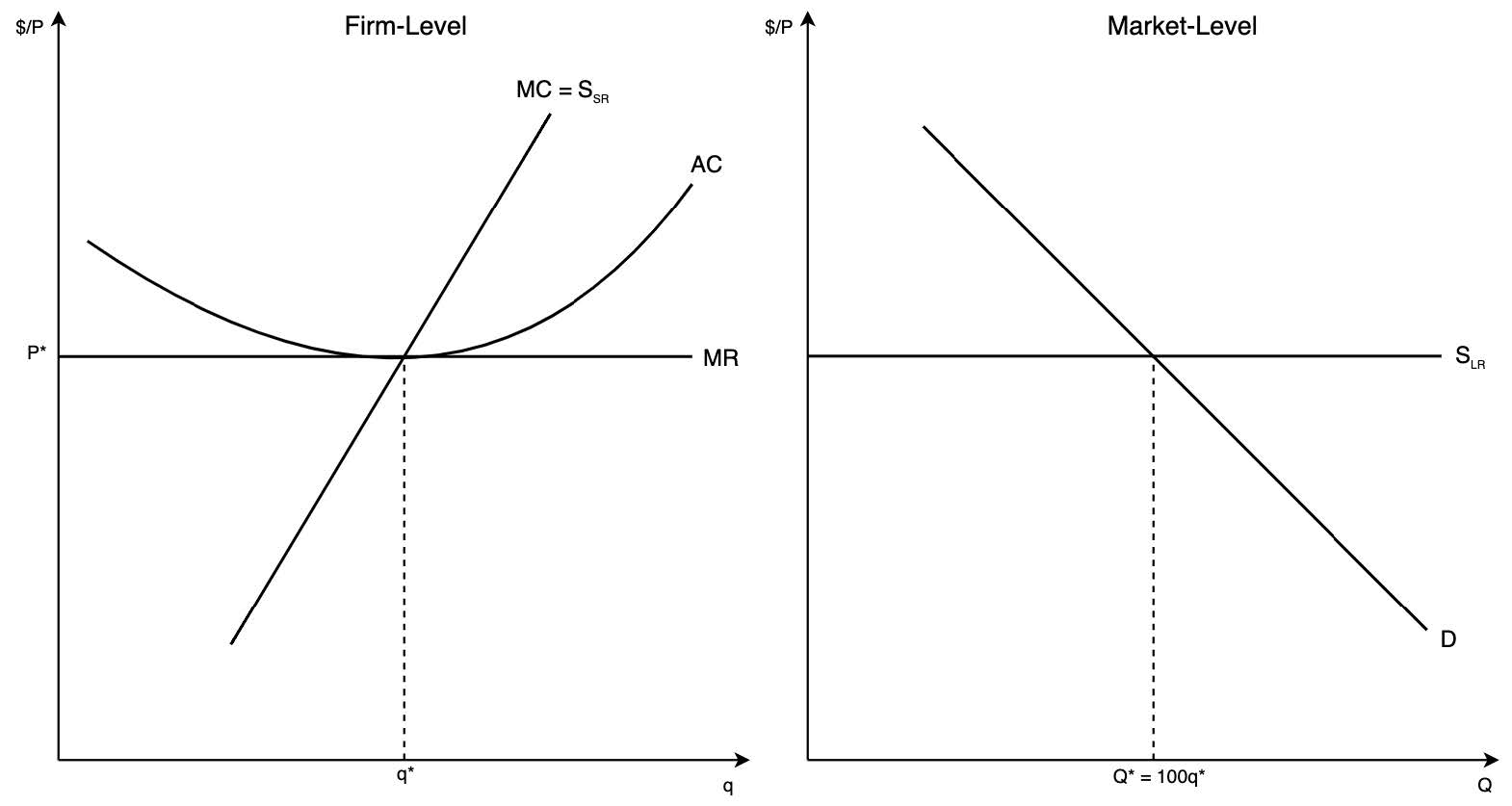

Perfect Competition

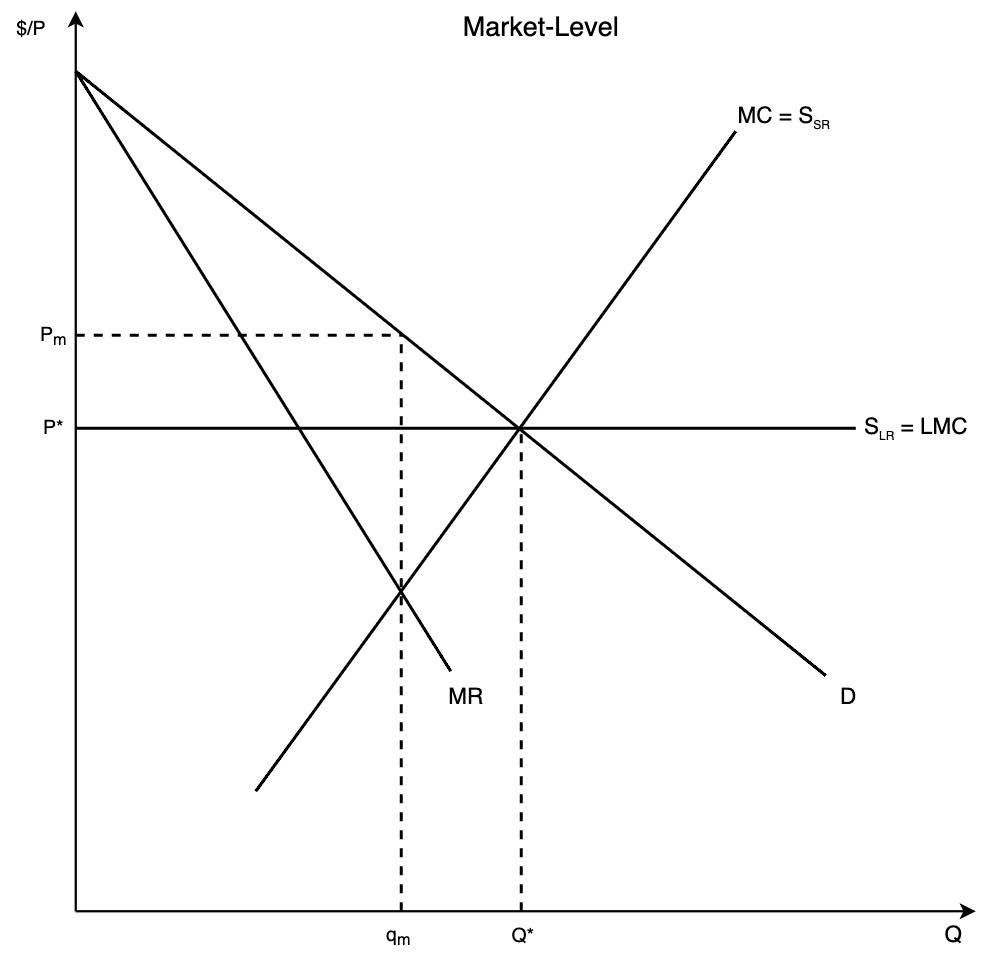

- Start by imagining a perfectly competitive market

- 100 firms exist, each with a single plant and identical production technology (i.e., same costs)

- This means each firm will produce 1% of total output (i.e., each firm supplies 1/100 of total production)

- The long-run equilibrium are shown in the figure below (similar to what we did the first week of class)

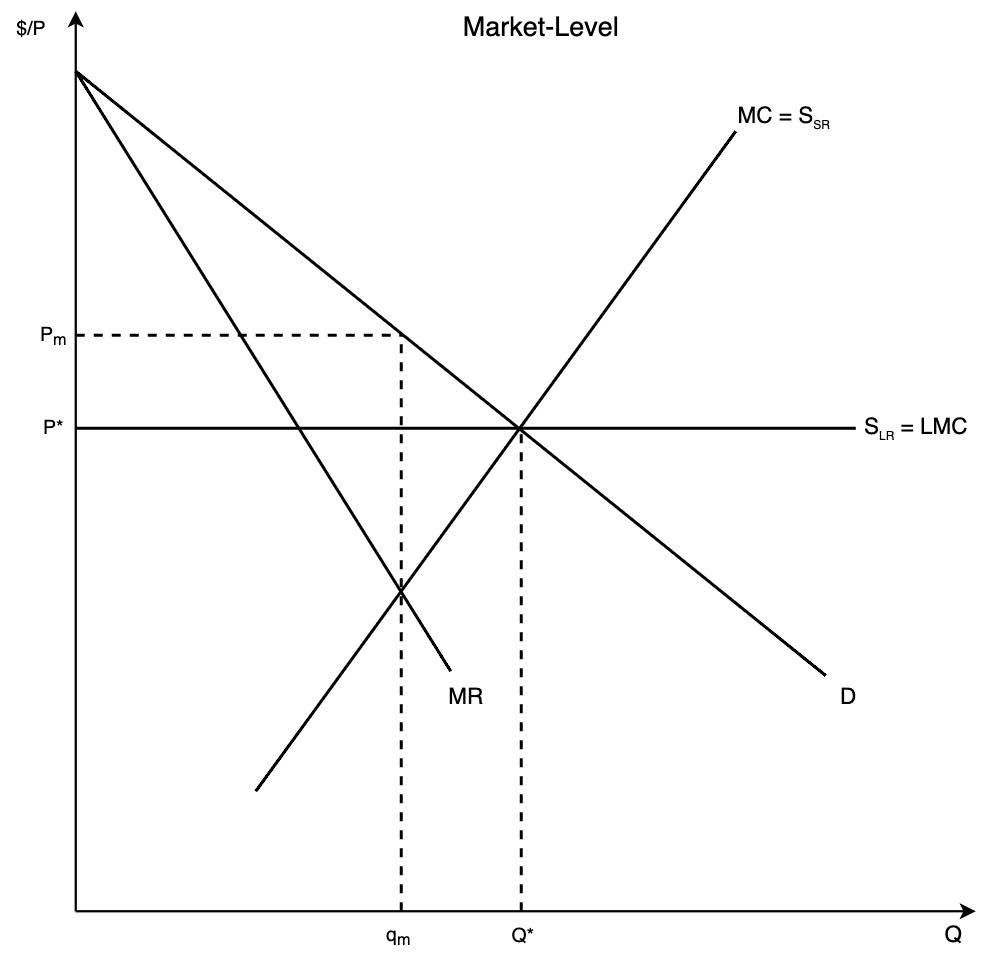

Mutliplant Monopoly

- Now suppose a monopolist exists and buys all 100 firms

- The monopolist can allocate production across plants however they choose

- Producing at the optimal level and setting price according to market demand leads to a higher price, lower output, and less welfare

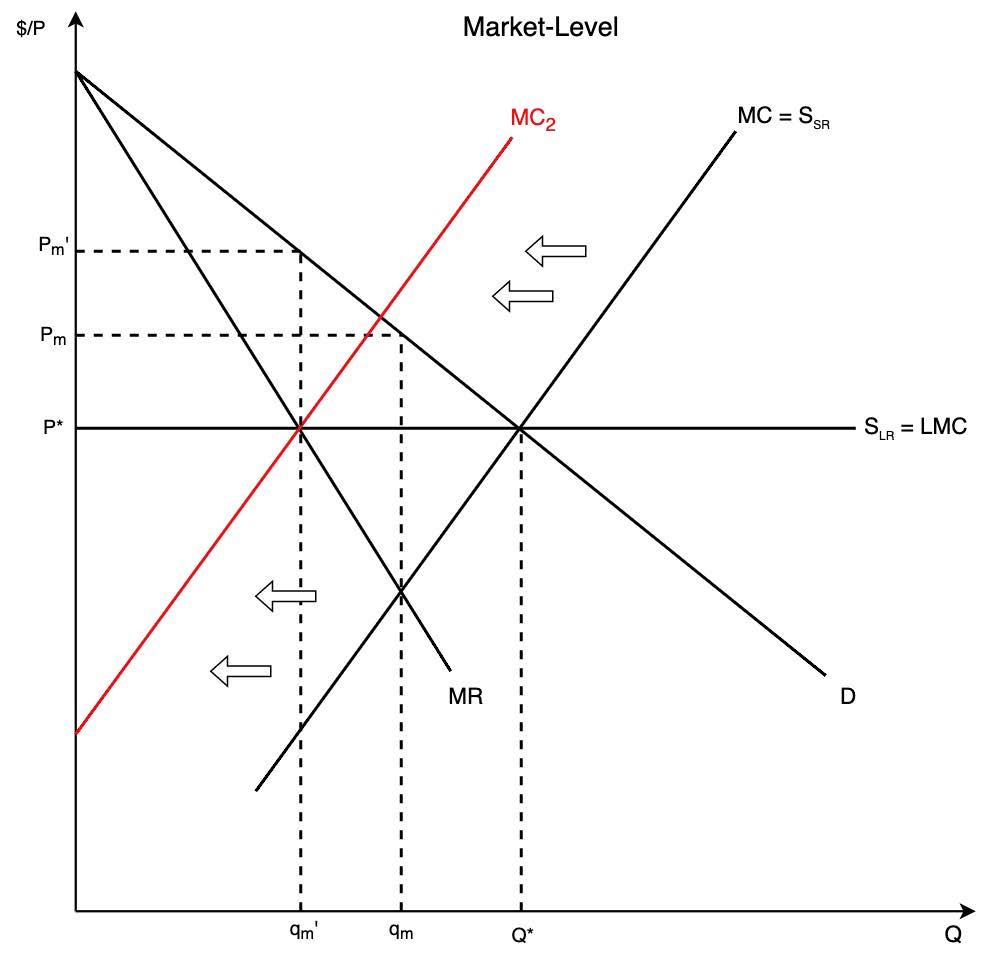

- The monopolist doesn’t start in LR equilibrium because \(MR \neq LMC\)

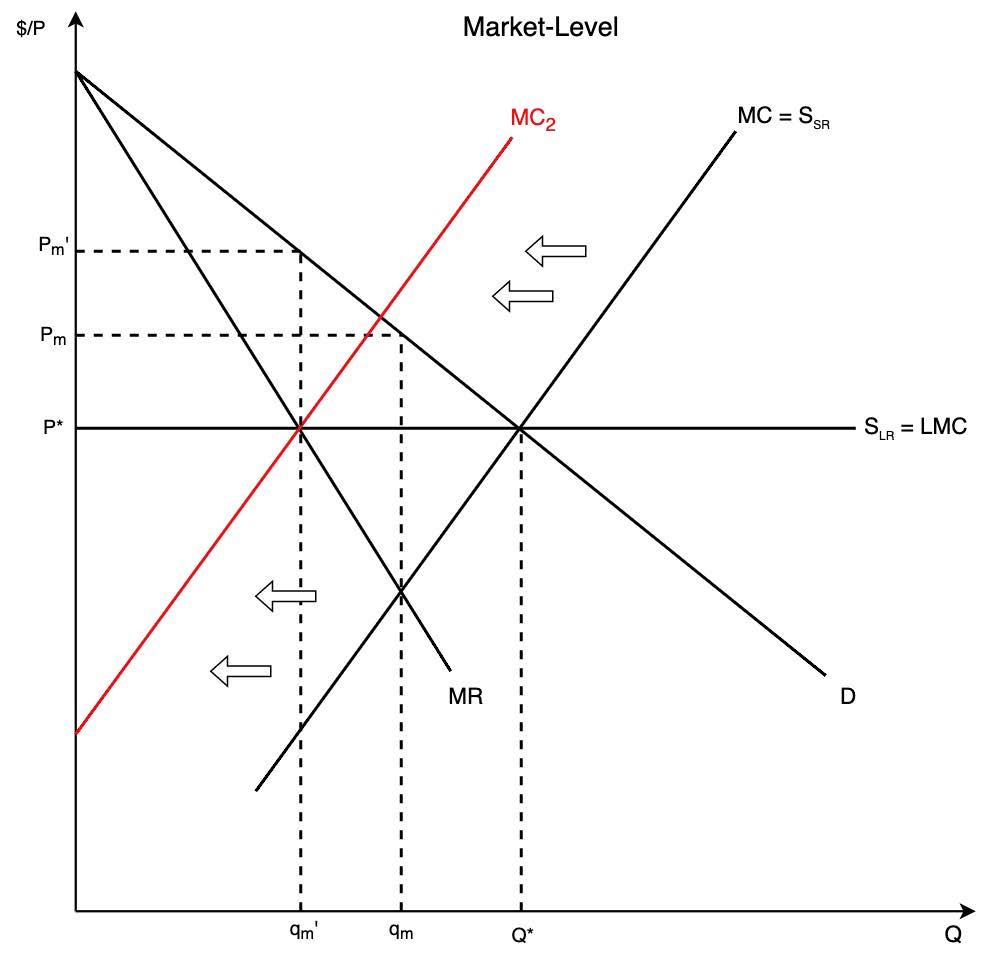

- The monopolist will sell off enough plants to decrease marginal cost (short-run supply) until \(MR = MC = LMC\)

→ This will lead to even more social cost

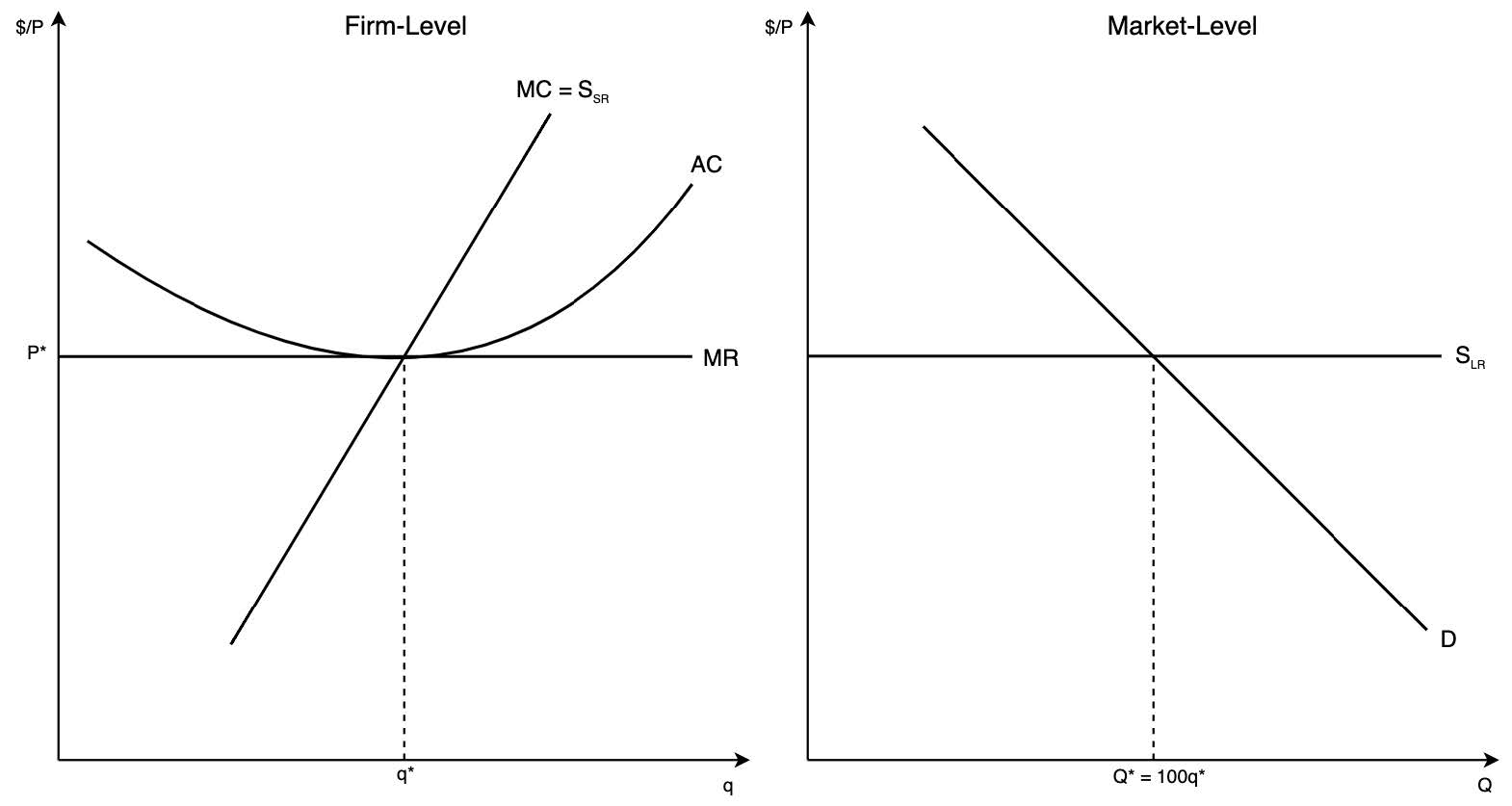

Cartel Theory

- A cartel consisting of 100 firms is analytically equivalent to a monopoly that owns 100 plants

- In the short run, this leads to the same price and output of a multi-plant monopoly

- The cartel chooses the total amount of the good to provide to the market

- The cartel agrees on a price to charge

- By working together, they allocate production in a way that minimizes cost

- Although the cartel and monopoly outcomes are the same in the short run, they are not the same in the long run

- In the short-run, firms cannot enter or exit

- In the long-run, entry can occur and entrants choose to join the cartel. This will continue until profits are driven down to the competitive level, where there is no more entry.

- The long-run equilibrium of the cartel can be characterized by excess capacity and overinvestment.

- Only the efficient member of the cartel will produce

- In order to maintain cooperation, excess profits may have to be shared equally among members