Damages

Measuring Damages

Courts have focused on damages as a means of compensating antitrust victims

- If an antitrust violation causes a business to lose profits, the business can sue for the value of lost profits

- If a firm or a consumer has paid too much for a good or service due to an antitrust violation, the suit will be for overcharges

- In either case, the courts focus on the wealth transferred to the monopolist from the buyers

While this may help with determent, or help a specific firm/person recoup losses, it doesn’t yield the “correct” amount in terms of the social cost caused by the antitrust violation.

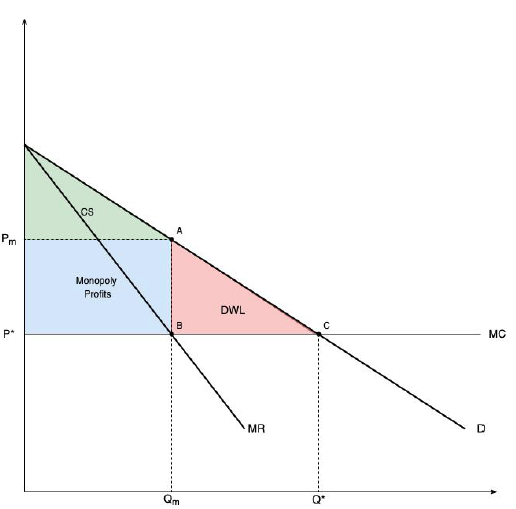

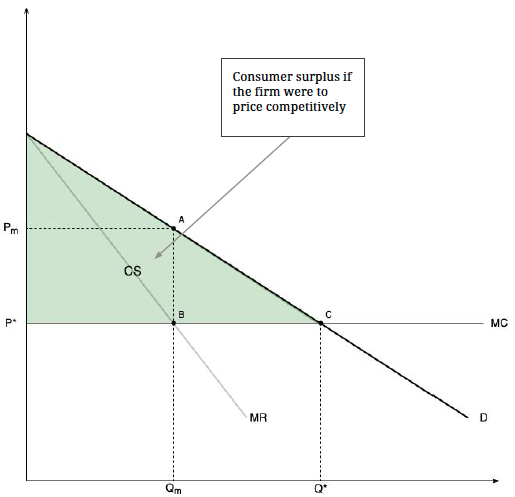

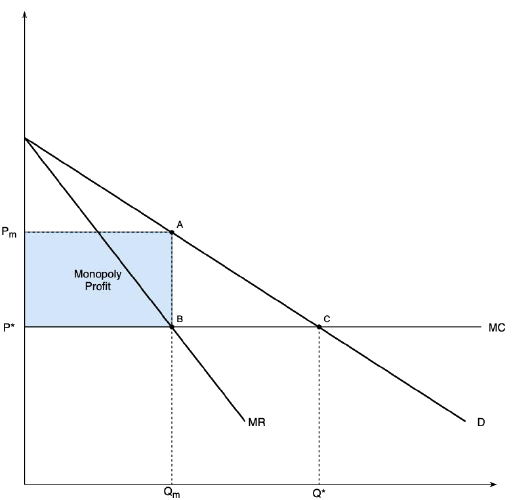

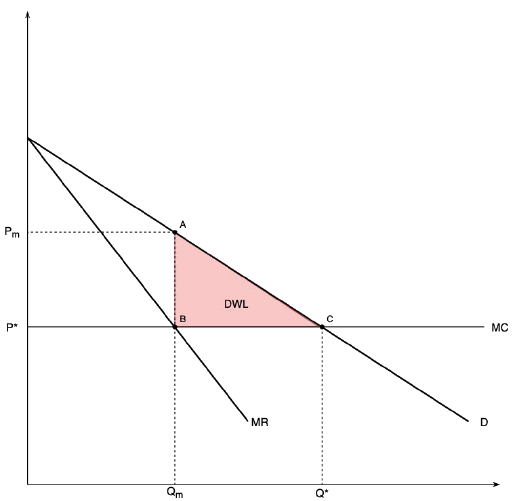

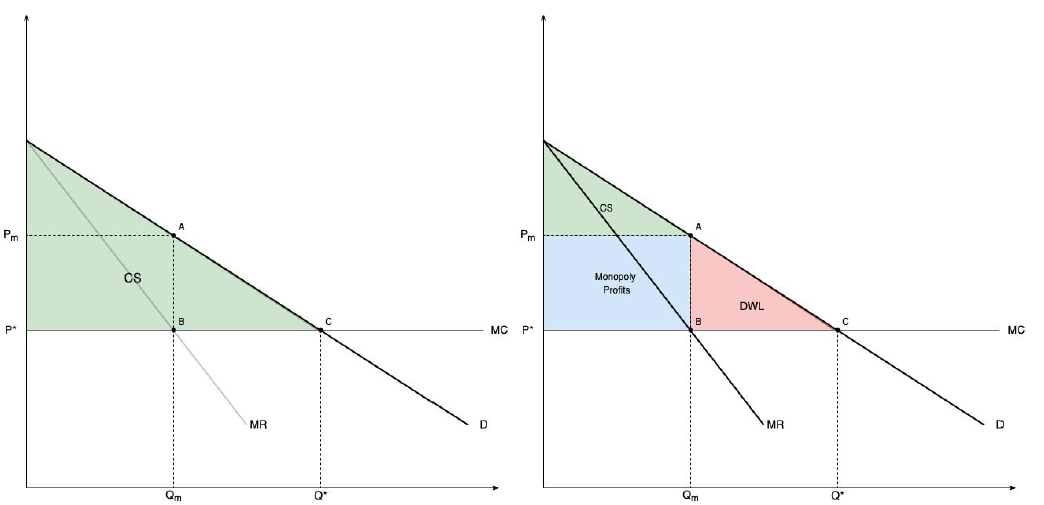

Consider a firm operating in a market described by the following graph where they can choose to operate as a monopolist

The wealth transfer from the consumers to the monopolist is given by the increased profits. This would be the customary measure of damage.

The cost to social welfare associated with this specific antitrust practice would be given by the deadweight loss

Treble damages is meant to cover the deadweight loss and may reflect under-enforcement risk

Proving Antitrust Damages

A plaintiff must prove 3 things to win an antitrust case:

- Liability Phase: prove an antitrust law was violated

- Impact or fact of injury: prove the plaintiff was injured by anticompetitive consequences of the antitrust violation

- Quantify the damages: the plaintiff is required to give a just and reasonable estimate, backed by evidence, not speculation.

The plaintiffs are held to a standard of “reasonable certainty” (that the injury was caused by the defendant’s action with reasonable certainty)

Types of Damages

Overcharge Cases

- The defendant illegally imposes a noncompetitive price on products purchased by the plaintiff

- Damages are equal to the overcharge multiplied by the quantity purchased

- The overcharge is the difference between the actual price paid and the price that would have been charged “but for” the violation

Foreclosure Cases

- The defendant excluded the plaintiff from the market through illegal means

- Damages are the difference between the plaintiff’s actual profit and the plaintiff’s profit “but for” violations

“But for” damage estimation

- “But for” estimation refers to estimating the world as if everything were the same except for the illegal activities (i.e. counterfactual)

- When estimating, the model assumes the only thing that changed was the presence of the antitrust violation.

- All other things that happened in the world exogenous to the violations remain the same

“But for” damage estimation: graphical explanation

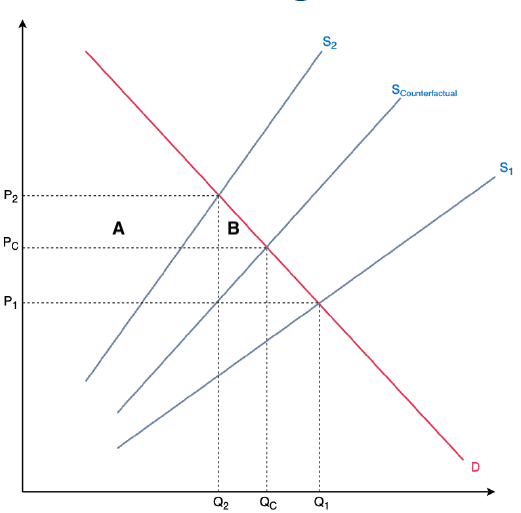

Consider a market described by the figure on the left.

\(S_2\) describes supply in the state of the world where antitrust behavior occurred.

\(S_1\) describes supply in the state of the world before antitrust behavior occurred

\(S_{\text{counterfactual}}\) describes supply in the state of the world today if the antitrust behavior never occurred.

If an antitrust suit were to follow, the subsequent damage estimation would need to use the “but for” price (\(P_c\)) and not the pre-violation price (\(P_1\))

Overcharge is the difference between price actually paid and the price that would have been paid “but for” the antitrust violation.

The plaintiff’s damage should equal the rectangle \((P_2-P_c)Q_2\) and not the \((P_2-P_1)Q_2\).

Even though the total welfare loss generated from the overcharge is represented by area in triangle (B), damage is generally defined by the excess profits illegally collected by the violators (A). Thus the total damage is given by the difference between \(P_2\) and \(P_c\) (overcharge per unit) times the amount sold (\(Q_2\))

Net Harm

- An antitrust violation can result in both benefits and costs

- The total damage payout must only be calculated off of the net harm of the violations

- Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum Commission v. National Football League (1986) set precedent for net harm

- The NFL requires 3/4 approval from owners to allow a team to move cities

- The Oakland Raiders and the LA Coliseum claimed the owners conspired to block Oakland from relocating to Los Angeles

- The LA Coliseum lost revenue from not hosting games but also didn’t incur the costs of hosting games

- The Supreme Court ruled the Raiders and the LA Coliseum could only receive damages for their net loss

Methodologies

- There are two basic methodologies for measuring antitrust damages and calculating the “but for” outcome

- Before-and-after approach: compare profits earned (or prices paid) by the plaintiff before and after the violation.

- Yardstick approach: use actual data on market performances in places where the violation did not occur

- Both approaches are inherently flawed

- Modern econometrics attempts to overcome these flaws

Flaws with damage estimation methodologies

- Before-and-after assumes the only thing that changed was the presence of the violence

- Outside events that happened at the same time as the violation could give an inaccurate estimate of the effect of the violation

- Yardstick model is ideal if you can analyze a clone of the plaintiff ‘but for’ the violation

- This is literally impossible to do

- A substitute is to analyze an entirely distinct market with a lot of the same characteristics

- The market must sell the same product and be located far enough away so that it’s not influenced by the violation